They say that nearly all movies date, just some quicker than others. Think of the number of thrillers that, before mobile phones, revolved around telephone boxes, couples sleeping in separate beds, or the stop-motion special effects of the 1960s. These things might look quaint now, but they’re usually harmless reminders of the era in which a film was made.

Where things become more troubling is when a film’s view of love and relationships doesn’t just look old-fashioned, but actively creepy. When it feels so out of step with modern values that it borders on the offensive, nostalgia stops being charming and starts becoming uncomfortable. Unfortunately, Love Actually falls firmly into this category.

The main problem for me is that almost all of the women in the film seem reliant on men, either professionally or emotionally, and the men are almost always in positions of power over them. This dynamic isn’t questioned, challenged, or even acknowledged it’s presented as romantic.

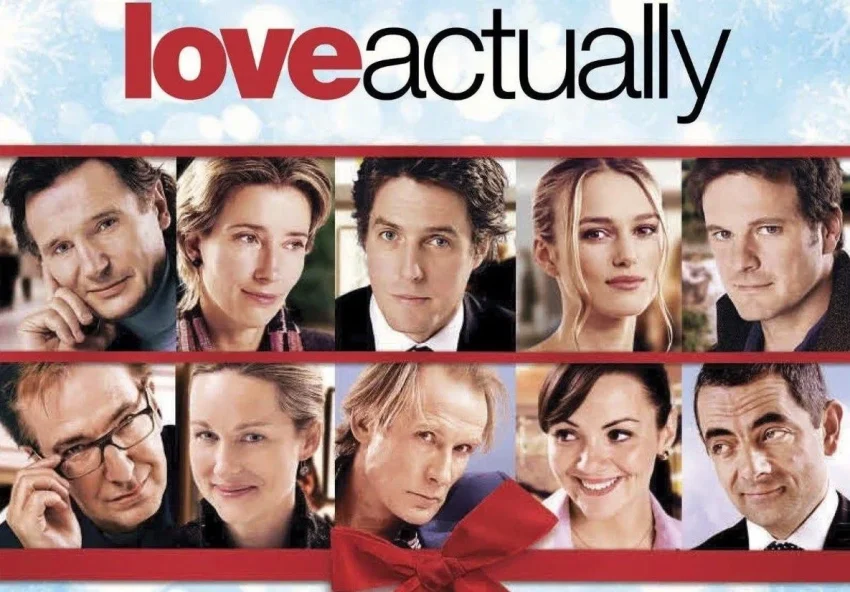

Take Hugh Grant’s Prime Minister and Martine McCutcheon’s lowly employee, whose entire arc revolves around being noticed and chosen by her boss. Or Alan Rickman’s character, casually debating whether to embark on an affair with his much younger female employee, treating her like a temptation rather than a person. Then there’s Colin Firth in his picturesque French cottage, falling in love with his housekeeper a woman he cannot even communicate with, yet somehow knows intimately enough to marry.

The creepiness peaks with Keira Knightley’s storyline, where her husband’s best friend secretly harbours feelings for her and turns up at her house late at night to declare his love. This is framed as romantic restraint, when in reality it feels like a betrayal wrapped in a cue-card gimmick. Even worse is Liam Neeson encouraging his young stepson to pursue what he believes is love by effectively stalking a girl he barely knows. Played for laughs and sweetness, it now feels wildly irresponsible.

Just because a film is set at Christmas doesn’t mean it embodies the spirit of the season. The weirdness continues with the repeated fat-shaming of Martine McCutcheon’s character, who is referred to using terms like “Miss Dunkin’ Donuts” and “plumpy” insults that are never challenged and are somehow meant to be endearing.

I don’t mind films with sprawling casts and intersecting storylines. It’s almost impossible for there not to be a few cardboard cut-out characters. But when something is sold as a romantic comedy, the characters should at least be vaguely likeable. Too often here, they simply aren’t.

To be fair, this isn’t new territory for Richard Curtis. He did much the same in The Boat That Rocked, where female characters largely exist as fans, sexual rewards, or people tricked into sex.

Some movies are ahead of their time. Some are of their time. And some should have been left in the script drawer.

This is one of them.